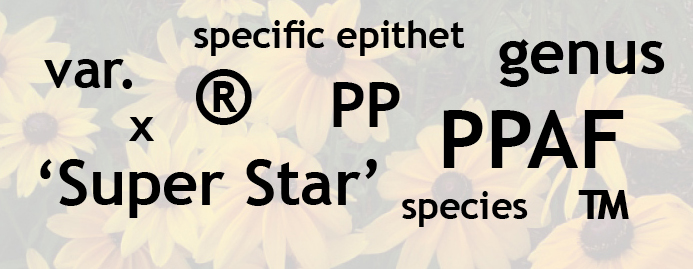

Yesterday we answered why there are two names for plants. Today I want to know, are some of the other details in plant naming confusing? How do you know what word to capitalize? Why are some words in quote marks? What’s the difference between a trademarked plant and a patented plant? And what’s up with those abbreviations and numbers on some ID tags?

Capitalization

According to The Mayfield Handbook of Technical and Scientific Writing, it is proper to capitalize and put in italics the genus of plants; yet, do not capitalize the specific epithet or the common name. There are exceptions to this rule which can be lengthy to explain, but you’re generally safe only capitalizing the genus and any proper nouns. Example: Aralia racemosa or American spikenard. Cultivars are also commonly capitalized.

What is a cultivar? The term is derived from the words “cultivated variety” and according to Oregon State University, is defined as: “an assemblage of cultivated plants which is clearly distinguished by one or more characters, and which when reproduced retains its distinguishing characteristics."

Quote marks

In addition to being capitalized, cultivar names are the portions of plant names you’ll find highlighted with single quotes. As a side note, you might recognize that cultivar names are not italicized like their friends the genus and specific epithet are.

An example of a plant name with its associated cultivar is ‘Crimson King’ Norway maple (Acer platanoides ‘Crimson King’).

Patented plants

Cultivars that are patented have the letters “PP” and a series of numbers following the cultivar name. For instance, Euphorbia 'Ascot Rainbow' PP21401 is patented and its patent number is 21,401.

You may also see the letters PPAF following a plant’s name. That stands for “plant patent applied for.”

Patented plants can only be grown by the grower that originated the cultivar (or by growers they choose to license) for 20 years following the receipt of the patent.

Trademark names

Both patented and unpatented plants can be trademarked. With trademarks, federal protection isn't applied to the growing of plants, but instead to their names in order to indicate a proprietary source of origin. It is used to set apart or brand a particular grower from other growers. An example of a trademarked name is The Knock Out® rose. Notice the ® symbol? That means this trademark has been federally registered. If you see a ™ symbol, it hasn’t.

Varieties (var.)

Like a cultivar, these plants have characteristics unique from their species. Unlike cultivars, those characteristics came about on their own in nature – not as a process of selective breeding by humans.

Hybrids (x)

Sometimes it is possible to obtain a new offspring by crossing two species. When this is done, the “x” falls between the two words in the name. Example: Fragaria x ananassa is the cross between two strawberries; Fragaria chiloensis and Fragaria virginiana.

Occassionally, growers can produce a cross-genus hybrid. When this happens, the “x” is placed before the genus in the name. Example: x Fatshedera lizei is the intergeneric hybrid of English Ivy (Hedera helix) and Japanese Fatsia (Fatsia japonica).

Is that enough to keep your head spinning? It is for me! And now you’ll know what you’re looking at next time to review the tags on your next plant purchase. Happy landscaping!